Retour informé vers les débuts de l'industrie cinématographique canadienne et son studio Associated Screen News basé à Montréal. Un programme exclusif de 13 films incluant 10 restaurations inédites.

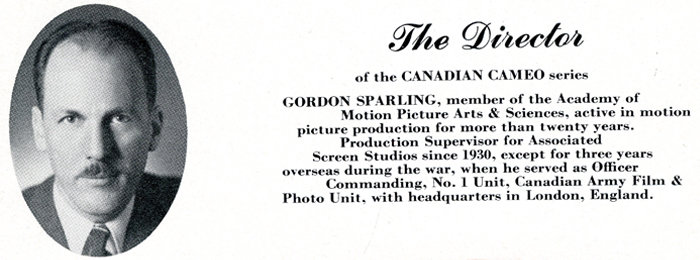

Dans une lettre en date du 28 octobre 1982 adressée au collectionneur Jean Bélanger, le cinéaste Gordon Sparling se désole du manque de considération accordée au patrimoine cinématographique canadien : « It was only a couple of decades ago since nobody seemed to give a damn about preserving our motion picture history. For a long time I was one of the very few small voices crying in a very large wilderness. You were one of the pioneers who not only said ‘save our old pictures’ but did something about it. » [i]

Jean Bélanger détenait alors ce qui était probablement la plus importante collection privée de films au Canada. Au-delà de son ampleur, cette collection se démarquait par sa variété : alors que la plupart des collectionneurs de films de son époque se concentraient sur la fiction et les longs métrages, Bélanger avait recueilli des milliers de copies de films gouvernementaux, industriels, publicitaires et touristiques, d’actualités filmées, de films amateurs, de films de famille et de courts métrages professionnels produits pour le marché domestique. On peut présumer que si Bélanger, qui ne disposait que de son salaire de policier pour financer ses activités de collecte, put faire l’acquisition d’autant de bobines, c’est qu’elles avaient acquis un statut de rebut ou de déchet au moment où il les ajouta à sa collection.

L’histoire de la collection Bélanger illustre ainsi parfaitement le sort des films dits « utilitaires » ou « éphémères » occupant une place centrale, mais longtemps négligée, dans l’histoire du cinéma au Canada. On trouve ainsi parmi les bobines récupérées par Bélanger plusieurs productions de la compagnie ayant pendant de nombreuses années été l’employeur de Sparling : Associated Screen News. Fondée au cours de l’été 1920 à l’initiative du Chemin de fer Canadien Pacifique — alors la plus importante compagnie privée du pays —, Associated Screen News avait deux missions centrales. La compagnie devait d’abord produire des films et du matériel visuel devant inciter des immigrants du Royaume-Uni et d’Europe du Nord à venir coloniser des territoires canadiens autrefois peuplés par les Premières Nations et les Métis. Associated Screen News devait ensuite faire la promotion des destinations touristiques du Canadien Pacifique, qui détenait de prestigieux hôtels dans plusieurs sites touristiques canadiens (Québec, Montréal, Banff, Victoria, etc.), de même que des liaisons avec l’Europe et l’Asie assurées par les paquebots de la compagnie.

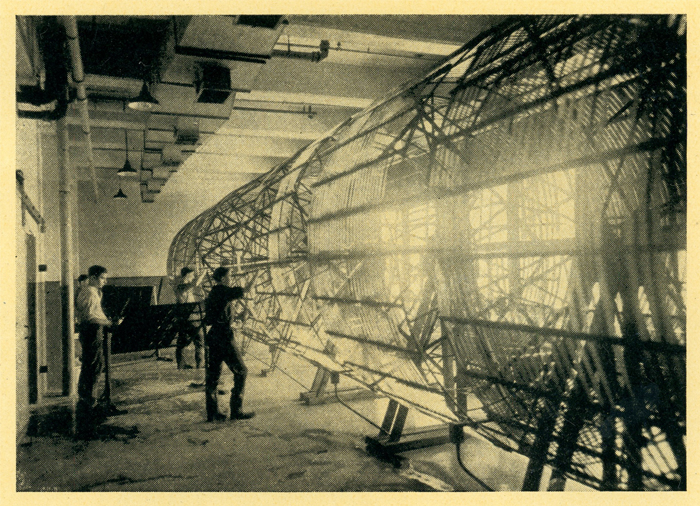

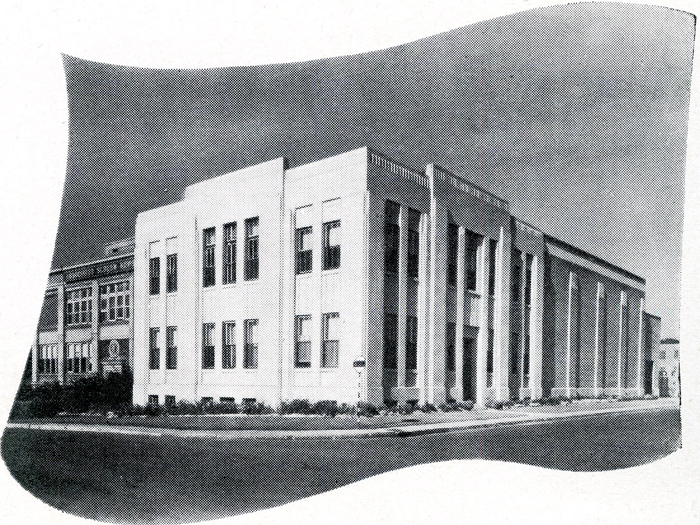

Les importantes ressources financières du Canadien Pacifique permirent à Associated Screen News de se doter rapidement d’importantes ressources matérielles, ainsi que d’assembler une importante équipe. D’abord installée dans l’édifice Albee situé à l’arrière du cinéma Imperial, la compagnie fait construire au milieu des années 1920 un imposant édifice se dressant toujours à l’intersection du boulevard Décarie et du boulevard de Maisonneuve Ouest, dans lequel elle installe son studio, ses ateliers, son laboratoire et ses bureaux. Huit opérateurs de prises de vues équipés de caméras Bell & Howell 2709 — le même modèle équipant alors la plupart des studios hollywoodiens — sont déjà à son emploi à travers le Canada au milieu des années 1920. Au moment où l’industrie cinématographique se convertit au parlant au tournant de la décennie 1930, ce sont plus de cent personnes qui travaillent dans les locaux de l’Associated Screen News à Montréal.

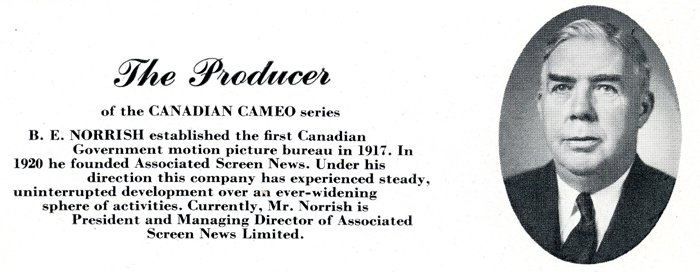

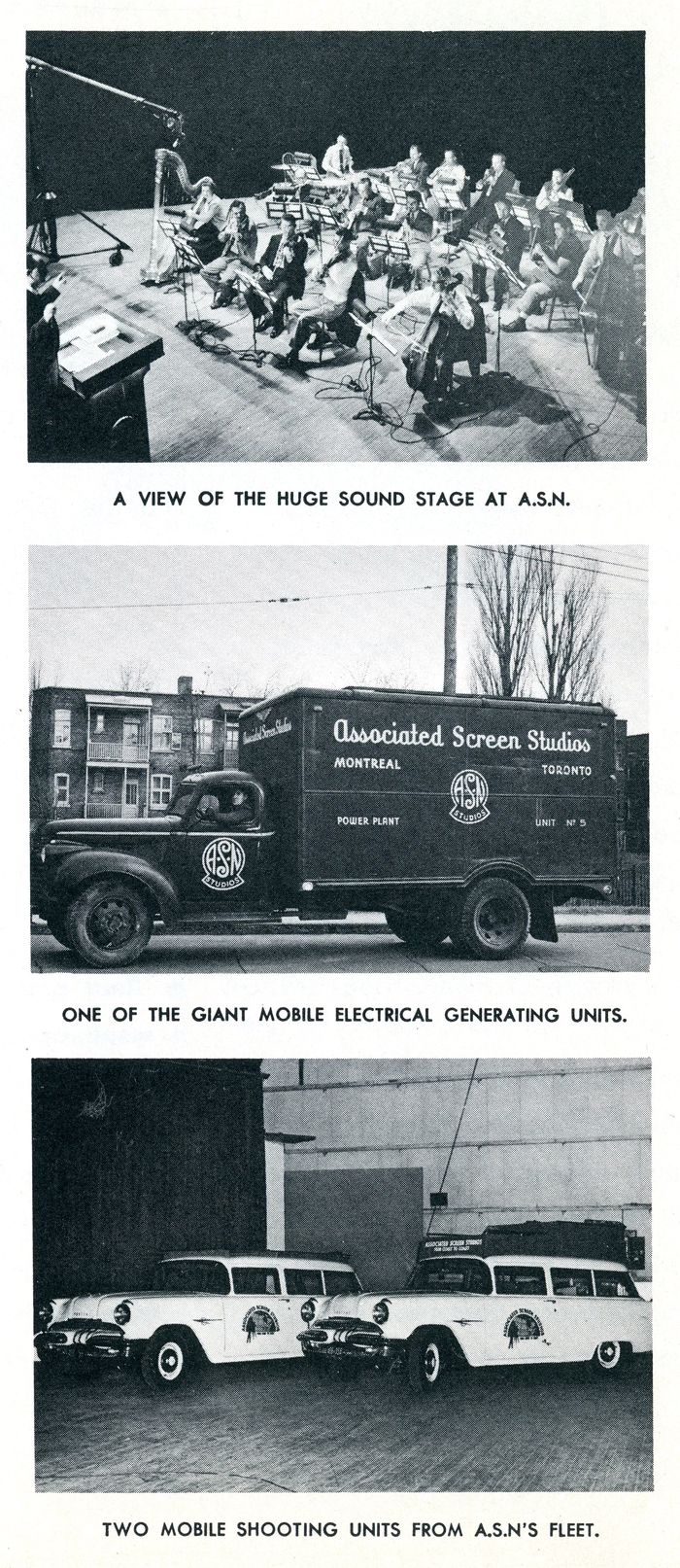

L’équipe dirigée par B.E. Norrish produira au fil des décennies des films pour le Canadien Pacifique, mais aussi des films publicitaires, industriels et de commande pour des industries canadiennes, de segments de journaux d’actualités couvrant des événements canadiens, ainsi que des séries de courts métrages destinées aux salles de cinéma commerciales — les Kinogram Travelogues, Camera Rambles et Canadian Cameos. En 1931, Associated Screen News s’équipe pour le son et ajoute à son édifice une extension abritant ce qui est alors le studio de prise de vues le plus perfectionné du pays. Celui-ci sera notamment utilisé en 1941 par le réalisateur britannique Michael Powell pour le tournage de séquences de 49th Parallel, un long métrage de fiction co-scénarisé par son collaborateur Emeric Pressburger.

La production de films ne génère toutefois qu’une partie des revenues d’Associated Screen News. La compagnie, qui a tout intérêt à voir le cinéma utilitaire et l’exploitation non commerciale prendre son envol, possède également une filiale dédiée à la vente de projecteurs et la location de films, Benograph. Les équipements et films qu’elle destine aux circuits parallèles sont en grande majorité de format 16 mm, mais un certain nombre de titres Associated Screen News seront également tirés en 35 mm sur support Safety diacétate pour exploitation en dehors des cinémas commerciaux.

La plus importante — et constante — source de revenus d’Associated Screen News semble toutefois avoir été son laboratoire, que la plupart des producteurs américains utilisent pour le tirage des copies d’exploitation de leurs films destinées au marché canadien. À l’époque du muet, ces derniers peuvent également y faire traduire les intertitres de leurs films. Le matériel publicitaire d’Associated Screen News prend à cet égard bien soin de leur rappeler que :

The experience of years of Canadian film distribution has shown the commercialnecessity of supplying feature pictures to be circulated in French-Canadian territorieswith bilingual titles.Foreign producers have often been betrayed into humorous but expensive errors byemploying translators to put their titles into Parisian French. The French-Canadians issome centuries away from France and has evolved a language and idiom of his own.Successful motion picture titles for Lower Canada must be written in that idiom.[ii]

Il est à cet égard intéressant de noter que, au cours des décennies qui suivront la disparition d’Associated Screen News en 1957, le laboratoire et les studios construits dans les années 1920 et 1930 seront utilisés pour la production de doublages par Bellevue Pathé.

Laboratoire d'Associated Screen News à Montréal durant les années 1920 (coll. Cinémathèque québécoise)

La diversité des services offerts et l’ampleur des moyens techniques déployés ne suffisent toutefois pas à expliquer le succès d’Associated Screen News, qui accomplit l’exploit de survivre comme entreprise cinématographique pendant près de quatre décennies dans le Canada du milieu du vingtième siècle. La première raison de cette réussite est sans conteste la qualité des personnes qui l’animent au fil des décennies. Le Canadien Pacifique prend à cet égard une décision clé en 1920 avec l’embauche de Bernard E. Norrish, qui dirigera Associated Screen News jusqu’à son départ à la retraite en 1953. Norrish était alors un des rares Canadiens ayant une véritable connaissance du monde du cinéma, puisqu’il avait eu l’occasion de diriger le Canadian Government Motion Picture Bureau créé en 1918 pendant ses deux premières années d’activité.

Norrish rassemble autour de lui une équipe formée d’un grand nombre de créateurs et techniciens de talent. Pendant quelques années au cours de la décennie 1920, la personne la plus en vue dans l’équipe Associated Screen News est nulle autre que Terry Ramsaye, qui avait travaillé avec Charles Chaplin chez Mutual dans les années 1910 et écrit une des toutes premières histoires du cinéma au début des années 1920 (publiée par chapitre dans Photoplay, puis rassemblée dans un volume intitulé A Million and One Nightsen 1926). Ramsaye est crédité pour le montage et la rédaction des intertitres de plusieurs productions Associated Screen News. Son nom apparaît au générique de plusieurs des films de la compagnie sur le même carton que le titre, ce qui témoigne de l’importance accordée à ces fonctions, qui sont alors essentiellement assimilées à celles de réalisation.

Associated Screen News mettra quelques années à remplacer Ramsaye après son départ à la fin des années 1920. Norrish frappera toutefois un grand coup en 1931 avec l’embauche de Gordon Sparling. Bien qu’âgé d’à peine trente ans, ce dernier avait déjà près d’une décennie d’expérience dans le monde du cinéma, ayant travaillé pour l’Ontario Motion Picture Bureau et tourné pour l’Association canadienne de foresterie, été assistant de Bruce Bairnsfather — dont il critiquera sévèrement le travail — sur le tournage de Carry on, Sergeant! en 1928, puis passé quelque temps dans les studios new-yorkais de Paramount au tournant des années 1930. Sparling, qui restera à l’emploi d’Associated Screen News jusqu’à la fin des activités de la compagnie en 1957 (à l’exception des trois années durant lesquelles il dirigea les services cinématographiques de l’Armée canadienne pendant la Seconde Guerre mondiale), injecte une bonne dose de créativité et d’imagination dans les sujets souvent prosaïques qu’on lui confie. Une de ses plus grandes réussites, Rhapsody in Two Languages (1934), transforme ainsi un vulgaire travelogue devant convaincre le public américain de venir profiter de la vie nocturne montréalaise en une glorieuse symphonie urbaine utilisant à fond le potentiel de la caméra, du montage et de la bande-son. L’indéniable talent de Sparling permettra à plusieurs productions Associated Screen d’avoir de respectables carrières commerciales dans les salles de cinéma du Canada, mais aussi des États-Unis.

Brochure Canadian Cameo de 1949 (coll. Louis Pelletier)

Plusieurs des autres artisans du cinéma recrutés par Norrish resteront de nombreuses années à l’emploi d’Associated Screen News, et auront par conséquent un impact important sur les films produits par la compagnie. Maurice Metzger, qui avait d’abord collaboré à la production de la série de films Living Canada tournée par les Britanniques Joe Rosenthal et F. Guy Bradford à l’initiative du Canadien Pacifique en 1902 et 1903, joue pendant de nombreuses décennies un rôle central dans les opérations du laboratoire et du département son. La musique occupant une place centrale dans un grand nombre de productions Associated Screen News tournées à partir du début des années 1930 est pour sa part composée par des musiciens bien en vus au pays, dont Howard Fogg et Lucio Agostini (qui s’illustre également comme chef d’orchestre d’Alys Robi). Une pionnière méconnue du cinéma canadien, Margot Blaisdell, signe quant à elle le scénario d’un grand nombre de productions Associated Screen News. Les prises de vues sont par ailleurs assurées par un groupe d’opérateurs de talent comprenant notamment John M. Alexander, Roy Tash (qui fut le cameraman attitré des jumelles Dionne), Alfred Jacquemin, Lucien Roy et Frank O’Byrne. Ces opérateurs postés à travers le Canada feront à partir des années 1930 un grand usage de la flotte de camions équipés pour la prise de son en extérieur détenue par Associated Screen News.

L’Office national du film du Canada et le Service de ciné-photographie de la province de Québec, respectivement créés en 1939 et 1941, reconnaîtront la valeur du personnel d’Associated Screen News et confieront à la compagnie la production de plusieurs films gouvernementaux dans les années 1940 et 1950. La grande stabilité de l’équipe rassemblée par Ben Norrish a toutefois un effet pervers, puisqu’elle place Associated Screen News dans une situation lui permettant difficilement de s’adapter aux changements importants qui se dessinent dans le monde du documentaire et cinéma du réel à la fin des années 1950. La compagnie tournera des films et séries pour la télévision, mais ne prendra pas vraiment le virage vers les tournages utilisant les appareils 16 mm portables associés avec le cinéma direct. Interrogé en 2010 sur ses rapports avec l’équipe d’Associated Screen News, Michel Brault déclara par exemple que ceux-ci avaient tout simplement été inexistants [iii].

Après avoir produit plusieurs des films canadiens les plus intéressants de l’époque du muet et des premières décennies du parlant, la compagnie cesse ses activités en 1957, quatre ans après le départ à la retraite Ben Norrish et le passage du contrôle de la compagnie du Canadien Pacifique à Paul Nathanson, fils du fondateur de Famous Players Canadian et Odeon Theatres of Canada. Le patrimoine d’Associated Screen News sera au cours des décennies suivantes disséminé et largement oublié, en dépit des quelques rares rétrospectives organisées en archives au cours des décennies. Bibliothèque et Archives Canada héritera d’une masse importante de matériel déposé par Bellevue-Pathé et Astral Média, successeurs d’Associated Screen News, mais ce matériel reste lacunaire et aucune filmographie complète de la compagnie n’a à ce jour été produite.

Cet effacement de la mémoire concerne jusqu’à la compagnie responsable de la création d’Associated Screen News. Contacté en 2010 par une équipe de l’Université de Montréal désirant numériser et mettre en ligne quelques productions Associated Screen News, le Canadien Pacifique refusa de donner son autorisation. Les personnes responsables à ce moment n’avaient en effet aucune connaissance des activités passées de leur compagnie dans le secteur du cinéma, et craignaient par conséquent d’exposer le Canadien Pacifique à des poursuites en cédant des droits sur des films ne leur appartenant pas. La fille et héritière du collectionneur Bélanger, Carolle Bélanger, voit quant à elles ses démarches auprès des archives et cinémathèques échouer dans les années 2010. Aucun représentant d’archives ou de cinémathèque ne retourne ses appels, et elle doit se résoudre à mettre la collection de son père en vente à la pièce sur eBay et dans des bazars. Il incombera donc encore une fois aux collectionneurs de sauver ce patrimoine orphelin.

Références

Peter Morris, Embattled Shadows: A History of Canadian Cinema 1895-1939 (Montréal : McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1978).

Base de données filmographiques du Canadian Educational, Sponsored, and Industrial Film Project, Université Concordia, www.screenculture.org/cesif/